| A workflow process is long-running (days or years) and applies programming logic to human activity. |

An excellent example of a workflow system is a customer service department. Customers complain, and each complaint becomes a case or process. Certain things must be done in response to each complaint, but other things may be done optionally if the actual facts warrant it. Take a software maintenance department, for instance: for each bug report, front-line people must determine (1) if the bug is already known, (2) if there is already a change in the works, (3) if there is a known workaround, and so on. This may be a requirement for every complaint -- but if the front-line personnel don't know an answer, they may need to escalate the report to a tech support person. So in this case, there are certain required tasks, and certain optional tasks which are dependent on the current condition of the process.

A workflow process can be thought of as a running program (i.e. a system process) except for two things: a workflow case may be active for years if necessary (for instance, it may represent a major project or it may be held up waiting for further information), and most crucially, it defines and organizes human activity. The great promise of workflow, of course, is that it affords a tool whereby a complex organization can both document and enforce its own procedures. One of the basic motivations behind the wftk is to make this kind of high-power software available for very small organizations -- while there are already a boatload of workflow systems on the market, they are aimed at Fortune-500 companies and thus cost multiple boatloads of hard cash.

| The wftk is a free, flexible, extendable workflow toolkit. |

Enter wftk. The wftk, or open-source workflow toolkit, is a cheap (in fact, free) system to manage workflow. It is written to allow you the greatest possible flexibility in integration with your existing databases, directories, servers, and what have you. Using the wftk, you can create processes via definition or simple checklist, you can assign tasks by username or by role in your organization (or by role in a single process). You can delegate tasks by sending requests to people. You can do "ad-hoc workflow" by inserting arbitrary process pieces into your process. The wftk is intended to document and enable your existing practices, not force you to conform to somebody else's idea of the right way to do things, and ultimately the idea of wftk is to provide a decentralized solution to workflow, so that people can define and publish their own processes, and laypeople can maintain them as needed.

However, the wftk is also intended to work in very simple circumstances, which is why it's implemented as a library. Most websites, for instance, can benefit from active processes in some way, if only to keep track of problems (submit a problem report, and treat that as an active process. The webmaster can define a standard handling procedure, and when your web team grows to the point where several people need to coordinate their activities, then you simply redefine the handling procedure to include, say, a step where you assign the person who's to handle the problem.)

Another, more obvious, application would be to automate the approval process for new content in a content-based website. The wftk could easily treat each article as an active process, collect a couple of approvals, then automatically update the website. I'm looking at a couple of existing content-management systems with an eye towards integrating full-power wftk workflow into them, and I've also done some work (in the repository manager) to provide a simple content-management framework in native wftk.

| Workflow processes can get complicated. |

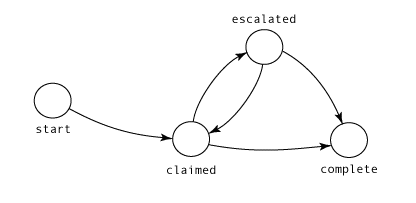

One of the basic problems that I have had while coming to terms with workflow systems is simply that there are two basic approaches to workflow. In the first, which was more strongly supported by early wftk prototypes, a process, once activated, then activates various tasks which must be done (this may include loops, decisions, and so forth, but the basic item here is the task.) Meanwhile, a lot of the material I was reading about workflow was firmly based in a transition-diagram model, where the process may be in a certain state, and the state of the process determined what various people might do. This dichotomy caused me a lot of grief before I realized that I was missing a point: state-based and task-based processes are simply different aspects of the same thing.

The crucial point to realize is that there are two types of action one may take at a given point when dealing with a case -- some actions may be required, while others may be optional. If required, they are governed by a task-based procedure (for example, when buying a house I am required to place an offer, the other party is required to respond, I'm required to fill out certain paperwork, and so on.) If optional, they are governed by a state-based description and the transition from one state to the next may involve required tasks. (In the house example, we might define a set of states that an offer may go through: proposed, accepted, rejected, in escrow, etc., and then imagine that at any point, certain parties to the offer may have actions they are allowed to do -- but that they have choices. Thus if the offer is in the "proposed" state, then the seller may optionally cause it to enter the "accepted" or "rejected" states, and either of those choices may require action from the seller, the buyer, or other parties.)

So a mature workflow system needs task-based (what I must do at any point in time) as well as state-based (what I can do at any point in time) description mechanisms. Not all do. The wftk does.

| Workflow makes your business logic independent of the systems you use to implement it. |

This is all pretty daunting if you are new to the idea of workflow, but here's the point: life consists of a lot of very complex processes. A workflow system allows you to define and document those processes -- and it allows you to do so without hard-coding your systems. The reason you care about that is simple: next year, your process will change. If your system is based on a workflow core, you simply define the change, and new processes will do the right thing automatically. If your system is hard-coded, you are faced with recoding and re-debugging.

Additionally, a workflow system implements a high-level description language for processes, which not only makes it easy to see where mistakes may be, but actually gives you fewer opportunities to screw up in the first place. Just as SQL and relational databases provide a standard way to deal with large masses of data, a workflow engine provides a standard way to deal with complex processes and situations.

An additional advantage to the wftk is that the wftk is designed to be able to work with a wide variety of peripheral systems. If you have a relational database, it'll happily use it (and it will work with any relational database) -- but if not, it'll do what it can. More to the point, if you start in a garage with no relational database system, define a bunch of processes, then next year you hire some staff and buy Oracle, your workflow process definitions need not change. Your business logic is independent of the data storage at your disposal, it's independent of the web server software, operating system, any aspect of the environment.

Let's imagine that our employee goes to request a chair, then. This request could be made in a number of ways, but let's assume this is

a web-based application, and to make the request, our employee submits a form. The form looks like this:

Now, when the process is started, wftk takes over and reads the definition of the chair request process. I'm not going to give the gory details in this overview document, because, well, then it wouldn't be an overview. No, instead, I'm just going to ask you to imagine what a secretary would do when a product request form is submitted, and then imagine that wftk is going to do the same thing. In the test case, the first thing to happen was that the requester's immediate supervisor would be asked to approve the request. In real life, there would probably be an approval from Purchasing or maybe the accounting department, but the upshot is this: when the process is submitted, it automatically creates an active task for the person or group which needs to approve the purchase. If approval isn't granted, the process dies an ignominious death and the requester is notified that the request was declined. If it's accepted, then Purchasing is notified of the request. Purchasing places the order, and maybe enters a purchasing record number into the process for cross-referencing. And so it goes.

The "traditional" way to develop this application would be simply to define a script (say) or other program, which retrieves the request, makes required entries in databases, and notifies people that something has happened. Then there would be other specialized programs which people would use to modify database entries and so forth. If the business process changes (maybe we discover that to comply with some law we have to notify the EPA, or maybe the tax codes change. Maybe we reorganize our business, or maybe somebody retires -- who knows? Things always change.) -- If the business process changes, then a programmer has to go in and modify the scripts. Maybe the whole design has to be modified. Regardless, it's going to be a lot of effort to get it all working again.

But with wftk, all you need to do is redefine the process. Currently active processes continue to work with the old version, and any new requests will be routed in the new way. The purpose of the wftk is to model what you do, and then automate it.

Task-based processes like this can be illustrated using flowcharts, or with other graphical conventions. I drew a role-action diagram during the prototype phase which illustrates the tasks required of various people or departments while the purchase process is going on.

Once escalated, a process may be returned to the original owner (an optional task for the specialist) or the specialist may simply decide to close the process directly. If the process is returned, it re-enters the "claimed" state, and note that the owner may then route it to some other specialist for some other reason -- an arbitrary number of times -- before finally being able to close the case.

At any point in this possibly lengthy process, by the way, arbitrary data values (even attached files and documents) may easily accrete in the process -- think of a really stuffed manila file folder. For this reason, the storage unit for a process is called a datasheet in wftk parlance. The infrastructure for data attachments is still somewhat sketchy at this writing, but I'm fleshing it out as I go.

This type of workflow is usually represented as a transition diagram. If you haven't studied computer science, you may not have heard this term, but think of each state as a circle, and possible transitions between states as arrows showing where the process is allowed to go at any point. Remember that any transition may be subject to any amount of task-based logic before it happens (to determine whether it really should) or after (to tell people that it did) and that logic isn't shown here.

If you're not a programmer, and you're seriously considering putting together any system based on open-source software, I heartily

recommend that you find a programmer. I'm usually available, by the way. Drop me a note at michael@vivtek.com

and I can help you get off the ground.